This article presents an argument that the cycle of centralisation (due to snowball effects [network effects, economies of scale {which also include things like shared blocklists on the Fediverse}]) and decentralisation is inevitable.

What is a scale-free network?

It shows that the scale-free networks get created, and that it is natural; that there is some sort of evolutionary force pushing towards scale-free networks. Scale-free networks follow a power-law; imagine a graph of Node Number against Number Of Connections, and arrange the nodes from the highest number of connections to the lowest, and a power graph will form.

Confusion point: The article seems to conflate scale-free networks with centralisation. Is this correct?

Scale free networks emerge because they’re efficient

This is something that p2p projects have repeatedly rediscovered. Flat networks perform poorly. Hubs are efficient.

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) networks have grown to such a massive scale that performing an efficient search in the network is non-trivial. Systems such as Gnutella were initially plagued with scalability problems as the number of users grew into the tens of thousands. As the number of users has now climbed into the millions, system designers have resorted to the use of supernodes to address scalability issues and to perform more efficient searches.

(Hadaller, Regan, Russell, 2012. The Necessity of Supernodes)

The average number of hops on a scale-free network is log(log(N)) for two random nodes, as opposed to a randomly-generated network where it is log(N).

Discussion point: Why do we need to care about “two random nodes”? For example, if we only care about nodes surrounding us (i.e. local culture), isn’t it more efficient to have it be more distributed?

My own thoughts

Two main points.

- The main thing about this is actually decentralising social interactions. Caring more about the content produced by people close to you, rather than influencers.

- You can build decentralised networks on top of centralised networks, but not the other way around. Let me explain…

We have a stack. Servers & ISPs (physical space) ← Domains (logical space) ← Social interactions.

Let’s make it easier to type: ISPs ← Domains ← Social.

Take a look at the ISPs; they are quite centralised. And on top of this centralisation, we’re able to build domains that are decentralised due to the log(log(N)) thing. By centralising, we can access random domains…

Or… take a single, centralised domain like Twitter for example. If you graph out the social graph stored in the database of Twitter, you can end up with something quite decentralised socially.

But! You can’t do it the other way around. For example, you can’t have a decentralised, P2P way of physically delivering internet packets, and build something centralised on top of it (eg an extremely popular server), because that will kill the network.

Possible same thing with the Domains ← Social part…

So. Decentralise social interactions first (perhaps this will already be naturally done by a lack of algorithm). Then you can decentralise the domains. And then the physical layer.

Scale-free networks emerge because of selection pressure

In an ideal distributed internet, we might all run personal servers from a closet. But we do not live in an ideal world, and running a reliable server is difficult. Computers crash, hard drives die, traffic will spike and your server get swamped. This is why people don’t want to run their own servers, and never will.

So, servers go down sometimes, and some go down more than others, and this is another reason scale-free networks emerge. Reliability, scalability are selection pressures. Fitter nodes attract more connections just by virtue of staying alive. Eventually this results in hubs. This is the Fitness Model of scale-free networks.

What about technological solutions like YunoHost, or in some cases where some nodes going down is not that big of a deal?

Hmm. My thinking is this. You have a ratio: PeopleDoingThings to PeopleUsingThings. Making things easier lowers that ratio. But it’s unlikely to be 1:1 (full P2P). Therefore, making things easier reduces this “selection pressure”, but communities still need to be formed – someone needs to be the admin, learn the skills to be the admin. The point is to make it easy enough that anyone can learn to do so on the side (and in the case of OSS it is definitely not easy enough).

Scale-free networks emerge because they are resilient to failure (yet vulnerable to attack)

Reminds me of this quote “decentralised systems are easy to hurt, but hard to kill.” Not too sure about this one, I don’t understand it well; as in, I don’t understand how this naturally creates scale-free networks.

Other articles

However, there are articles saying otherwise. This one says that, while on the whole the internet it does follow the power law, it actually varies across more local categories, and is closer to a unimodal (imagine a graph with a single bump) distribution.

As a whole, the World Wide Web displays a striking “rich get richer” behavior, with a relatively small number of sites receiving a disproportionately large share of hyperlink references and traffic. However, hidden in this skewed global distribution, we discover a qualitatively different and considerably less biased link distribution among subcategories of pages—for example, among all university homepages or all newspaper homepages. Although the connectivity distribution over the entire web is close to a pure power law, we find that the distribution within specific categories is typically unimodal on a log scale, with the location of the mode, and thus the extent of the rich get richer phenomenon, varying across different categories. Similar distributions occur in many other naturally occurring networks, including research paper citations, movie actor collaborations, and United States power grid connections. A simple generative model, incorporating a mixture of preferential and uniform attachment, quantifies the degree to which the rich nodes grow richer, and how new (and poorly connected) nodes can compete. The model accurately accounts for the true connectivity distributions of category-specific web pages, the web as a whole, and other social networks.

What are we talking about?

What even is centralisation and decentralisation? What are we even talking about?

- Social connections (includes both digital and real life)?

- Digital devices; clients and servers?

- ISPs? By the way, internet service benefits a lot from the log(log(N)), scale-free networks, power-law distribution thing. Only a few hops needed to connect any two internet devices in the world.

- Relations between open source projects?

- Knowledge bases (like this forum)?

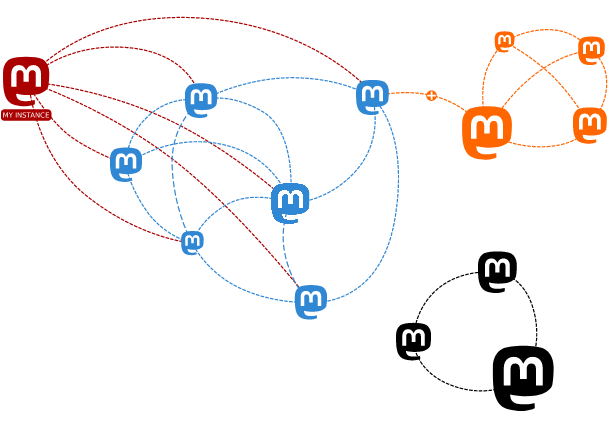

A mammoth amount of servers: Mastodon (de)centralisation

For a timely example, let’s say we’re talking about Mastodon servers. First of all. Do we care about centralisation?

- Perhaps yes, because a large server will have too much power over the entire Fediverse. They’ll be able to enforce their rules on other servers for example by threatening to defederate, or proceed at such a pace that other servers struggle to keep up (and they have to, since the large server contains many people). I’m not sure if this is entirely correct… can someone chip in?

The article claims that centralisation is inevitable due to…

-

Network effects. Hmm. This one is quite vague. It says “More users mean more users.” but that’s just the snowball effect in a nutshell. But the network effect in this case lies with the protocol.

-

Trust. People trust larger servers because they’re “too big to fail”, or like… they have more people and therefore more social proof. What about friendships? Would you trust your friend to host a server for you?

-

Economies of scale. This is my main concern. Indeed if you look at masto.host, the smaller servers need to pay much more per user ($1.20 per user for 5 users versus $0.45 per user for 2000 users). Sure, we could say “registration is free, so this doesn’t concern the users”, but this does concern the admins. Would servers band together so they share a lower hosting cost, or to share moderation efforts such as banlists and blocklists (which are also subject to economies of scale)?

-

I have said before somewhere that it’s nice that admins are community members because they have no incentive to defederate, and in fact encourage more servers; they don’t want to do everything by themselves (related: DoOcracy)! But what if an admin wanted to commercialise the server, and turn it into a for-profit? Perhaps the social force against that is the want for de-commercialisation… but even then, people would be convinced to use something that’s free rather than potentially have to pay for hosting out-of-pocket. See Github Pages.

- Perhaps then the limiting factor is the admin’s time and sanity, as a single human.

-

Use it or lose it

If we don’t make small servers/projects etc… the focus on big things, even if technically we can switch away, will eventually cause much effort in switching away.